Interview by RCR’s Jennifer Ortega. Follow Jen @jennifereortega

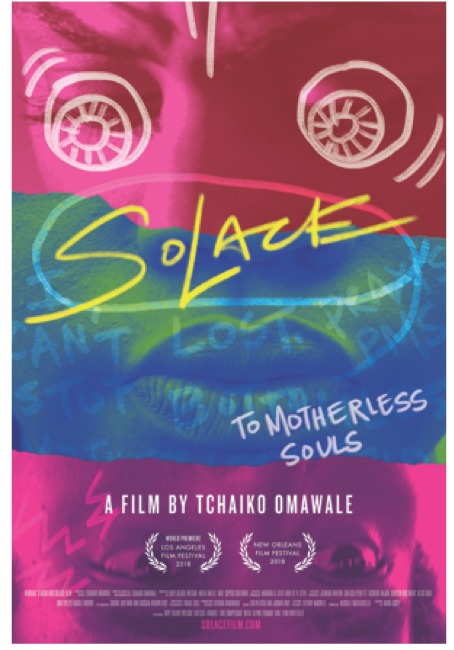

This year’s Los Angeles Film Festival promised diversity and different perspectives and at least in the case of director/writer Tchaiko Omawale’s film, Solace, it delivered. The film came from Tchaiko’s love of coming of age films yet never finding one as an adolescent that reflected her and the frustration in that. Solace is a visually provocative and emotionally raw film that deals with mental distress, death, isolation, cutting and eating disorders. “I wanted to make a film where I saw black girls dealing with that,” Tchaiko recently told Red Carpet Report during an interview. Hope Olaide Wilson gives a captivating performance as 17-year-old, Sole, who has many demons to deal with beginning with the death of her father. RCR’s Entertainment Reporter, Jennifer Ortega, recently sat down with Tchaiko and Hope to discuss the film.

Interview with director Tchaiko Omawale and actress Hope Olaide Wilson

Jennifer Ortega (JO): It’s so nice to meet both of you. I love the film. It was so emotional and real. There’s something very vulnerable and very honest about it. It started off as a short. You did a short first?

Tchaiko Omawale (TO): Yes. Yes.

JO: So where did the idea and the whole story all culminate from?

TO: It culminated from my darkness. It’s actually a weird story because I wrote the feature first. I was at a residency in Cape Cod and I actually had no eating disorder stuff in the original script then and it was just focused on the cutting because that was what I was dealing with and I wanted to make a film where I saw black girls dealing with that. So I wrote the feature and then I was like OK let me make a short film. And around the time when I started changing the feature script to make it into the short film that’s when I hit rock bottom with my eating disorder. So it was like OK, I need to put the eating disorder in there and then I started to see similarities as I became aware of my cutting ideations and what I did with food. I didn’t know how to make a feature right away because I didn’t go to film school so I did a short first. But the feature was always something I wanted to do.

JO: And Hope (Olaide Wilson) was in the short as well?

TO: Hopey, I call her Hopey sometimes. Hope was in the short. I stalked her on Facebook.

Hope Olaide Wilson (HOW): I’m no longer on Facebook.

Laughter

JO: So we can’t stalk you there anymore.

TO: I was George C. Wolfe’s assistant at the time and my casting director Aisha Coley was giving me a lot of different actresses. It was important for me that the actress not be physically overweight because I’m trying to show that eating disorders aren’t about the physical thing, but more about what’s going on inside. She presented Hope to me but was like her agents probably won’t let her read for you because this is a tiny film. So then I stalked her on Facebook and discovered that my cousin…So I was named after my family friend and her daughter who I call my cousin, Iabo. Iabo was friends with Hope on Facebook. So that’s how I found Hope. Lots of magic happened.

JO: I love that! I love that kind of serendipitous thing…it happens though when something’s meant to be.

TO: There are so many stories like this. I mean that’s how Lynn Whitfield came to the film. I love her. Queen Lynn.

HOW: I don’t know that story.

TO: You don’t know that story? So like I said I was George C. Wolfe’s assistant for a while. He’s a brilliant theater director and film director. I call him my mentor. And I would go, he would invite me to parties in New York. And I remember I was at a party and I was sitting next to Lynn Whitfield.

HOW: Oh my god! I didn’t know this!

TO: Yes, I was sitting next to Lynn Whitfield. There are so many stories. I knew Lynn Whitfield from Eve’s Bayou. That movie meant so much to me because I like dramas and dark emo things. I’m not so much into Romantic Comedies and Eve’s Bayou meant a lot. And so I was sitting on the couch next to her and something energetically…I don’t know, but her eyes, Lynn’s eyes. I just got sucked into her eyes. And I was just fascinated. I don’t remember what we talked about. It’s possible we talked about her daughter. I don’t remember. Years later when I was writing, when I was rewriting the feature and thinking about the grandmother character, Lynn was who I had in mind. When I was working with the first casting director on the feature, he was like why don’t you write her a letter. So I wrote this heartfelt letter about meeting her at George’s house and and how I wrote this part for her. And then she read the script and she was like if Glynn (Turman) does it then I’ll do it and then I met Glynn and Glynn and I talked a lot about my father. The same thing with Syd, Sydney Bennett. You know Syd from the music group. I wanted Syd to be in the film. I went does anybody know her. I asked the producer, do you know her. Nobody knew her. I called my friend, Chelsea. My friend Chelsea Peretti is one of the executive producers on the film and her friend Kojak is a music producer. I was like Kojak do you know Syd and he’s like no, but I know her cousin in Jamaica.

JO: I like all the cousin help that’s going on!

TO: It’s the cousins! I asked my mom because my mom was in Jamaica at the time, I said mom can you try to call this number. I was like trying to get everybody to call because I was broke and couldn’t afford to call Jamaica. And then finally I called the cousin and talked to him and he was like all right, let me talk to Syd. Then it was just like the right timing. I was perfect timing. I think it was right before she was going on tour for her solo album so she had time. Everything worked out.

JO: All of these little stories are kind of like really…they are magical things that don’t normally happen like every day.

TO: I’m a fairy.

JO: You really are! And Hope what was it like playing the lead character, Sole? I feel like that character is somebody that well, you deal with a lot of heavy stuff.

HOW: I keep saying I’m overwhelmed because I am. Just watching it is very uncomfortable just because I think I recognize so much of maybe not the specific things that she did, but I recognize so much of what she felt. I think just as an adolescent and even as an adult, just trying to be a part of something meaningful, trying to do something meaningful, but coping with so much hate and fear and frustration and trying to be strong on top of it. Being a person is really hard.

JO: It’s so hard!

TO: It is! That’s why I want to go away to the other dimension.

JO: I want to go to the other dimension!

HOW: I think what’s kind of amazing to me about it is that being a person is really hard, being a person just within the black community is very hard. This is like a magnified experience of this girl with the people around her, but then there’s still the outside world. That is a bigger thing to contend with. But showing just how intense and overwhelming life can be just within your family and within your immediate circle. It’s like oh my god, we haven’t even factored in the rest of the world. I think that makes it even more compelling for me and more overwhelming. But I I love it so much because it was a cathartic experience for me. I remember growing up and it’s like if you’re not quite…like you’re relatively normal in quotes, but if you’re not quite what people consider the ideal, if you’re not conventional, if your hair is not what it should be, all of these things that are just… all of this noise is being sort of thrown at you all the time. Then there’s feedback about not fitting into a neat box. I think that’s something that really resonated with me the most. I think from what I’ve heard from people watching it is that Sole doesn’t fit into a neat box. None of these characters fit into a neat box at all. I think that’s important. We put people into boxes. And again, that’s a coping mechanism because if we can recognize them and if we can define them in some neat specific way it helps us feel like OK, I know what you’re about, but when you’re not that then it’s triggering for the person that’s around you. And then it’s also triggering for the person who doesn’t fit into the neat box because they’re being told constantly to not be themselves because you’re not making other people comfortable.

JO: I love that and I do think it’s so relatable to so many people because maybe you’re not a cutter or not a drinker or whatever, but we’re all coping with something. And they’re all coping in the film differently. There is that piece of it that you will relate to no matter what you’re going through in life. But I do think it’s really important that you have a film where it shows cutting and eating disorders within a black cast because we don’t see that enough.

TO: You don’t. I don’t think you’ve ever seen that. I mean I think Zoe Kravitz may have played a character that had anorexia and Monique, the comedian, did a film back in the day when she was dealing with like her relationship with food. But this film, Solace, is very unapologetically like—-eating disorder—-cutting and central to it without it being like a PSA.

JO: Yeah. Which it’s not at all.

TO: It’s Kids, it’s literally, you know 13? It’s a movie that I love. Did you ever watch 13?

JO: Yes absolutely. I remember it clearly. It came out when I was still in film school.

TO: I love coming of age films. Coming of age films helped me cope with moving around the world and sort of like dealing with my identity because of all the emo stuff that teenagers deal with. But there were no black folks. There were no black people at all. And then the black films that started to come out, so I’m not American, I didn’t grow up here so I couldn’t really relate to like Boyz In The Hood. That was not my experience. And I have friends that have the experience that I put in my film. But our experience was not represented on screen. And that was so important to me. A lot of young black kids see this and they get it.They get it.

JO: I didn’t realize until I read your director’s notes that eating disorders among black girls, I think like 11 to 14 years old is so high. I had no idea.

TO: You wouldn’t know. The same thing with cutting. You wouldn’t know because here’s the thing, I was in therapy for my cutting ideations and I’ve been to a couple of different therapists, but how is it that I didn’t know I had an eating disorder until I was 30. This is the whole thing with representation. The health care providers can’t diagnose it if they don’t think that it’s possible that this is something I could be dealing with.

JO: That is infuriating.

HOW: It’s because it’s not reflected. What’s really interesting too is that because there’s so few reflections of ourselves on screen. Obviously, there’s more now. We’re getting there, but there’s always a sort of pressure because there’s a limited amount of representation, it has to be perfect, it has to be ideal, it has to be this beautiful, wonderful thing. It can’t be messy or if it is messy it’s a certain type of messy, it’s a certain type of drama. You know, I won’t specify, but there are certain kinds of dramas that we expect. But this movie is something I think that wakes you up because it’s like wait a second, it’s not this rosy picture, but it’s also not this indulgent like we’re going to milk a certain narrative because in some ways I think society wants certain types of black films because it alleviates guilt. So this film is just real and true. And hey, it’s showing that we are all actually very similar underneath. We all cope with things in this world. Yeah.

JO: I always think films like this are very authentic. There’s a beauty in that, that you don’t get from other types of films.

TO: Why else make art? Literally, each one of us has been put here because there’s a special journey we’re on and if you try to be like other people than what’s the point. You just hope other people like the thing you have been put to do here on Earth.

HOW: I’d like to ask Tchaiko a question. What has been the scariest part of making this film?

TO: Honestly, it has to do with money and having a kid. So I’m 40 and most female directors, I think there’s like a study or something, female directors if you’re going to pop it usually happens in your 40s. So you’re working so hard to pop in your 40s, but that’s also the time that your body is like…it’s the time when my body is like it has happen to now, getting pregnant. So there are these two things, career and child. I’m like oh my god what if this film does really well and then I have to choose between being a mother and being a director. That has taken the most amount, and money is involved in that, right, because if you don’t have financial support to make your film… like I can’t make another film the way I made Solace. The last four years of my life have been incredibly intense. There’s been a lot of labor on my body. I’ve had two miscarriages in the last year and it’s been intense. I can’t do that again. What I hope is that I have enough support so that I can make a film and have a kid at the same time and that honestly is the scariest thing. Also that old school notion of being a woman… because society is so unjust and for some reason, all of the society does not uphold women for the amazing beings that we are. We have to make these choices that are just ridiculous. Like what? I have to choose whether to be a mother or a director? And I have to do extra emotional labor to reprogram myself and just believe that no, Tchaiko, you can still direct, you’ll still be able to make the second film and still be able to have a baby. You will not have another miscarriage because of stress or whatever. What it did to my body, fighting this hard to get the film made, thank god I didn’t relapse.

JO: I really appreciate that you shared that. I’m a writer and I really relate to that. Every time I go to the doctor he asks me if I want to freeze my eggs.

HOW: How much does that even cost?

JO: Oh, like at least $8000. I have friends who’ve done it. But it’s like thank you, doctor, I am well aware of my age.

TO: You know it’s called geriatric pregnancy? Out of all the words, that’s what they pick I think once you’re over 35.

HOW: It’s called geriatric pregnancy?

JO: Oh yeah. Yes. Yes. All of my friends have not had children until they’re like in their late 30’s or 40’s.

TO: I mean that’s really normal in New York and LA . I think in different parts of the country people do it earlier. But when you’re not, I hope this is not wrong or bad or insulting to say but, a lot of the times when women are very focused on like accomplishing things yeah you’re waiting until you’re older.

JO: To me it makes sense to not have a child until older, you know at least in my life. But definitely it’s something I think about too. I’m really glad you said something. I think it’s very hard to balance everything.

TO: Have you seen that picture of Rachel Morrison hella pregnant? She’s the DP that did Mudbound. She was super pregnant shooting a film. That’s amazing and beautiful. My mother was dancing all the way, like all the way up until when she was giving birth to me. We’re awesome! Women are awesome!

JO: Your mother was a dancer?

TO: She was. I mean they’re retired, both of my parents now, but she was a dancer.

JO: Did that influence you in dancing?

TO: Completely. I mean dance was my first love. I wanted to be a dancer. Then I had body issues so I gave up. I also wanted to be an actress.

HOW: Did you really?

TO: You didn’t know the story? I wanted to be an actress, but I was like I can’t do something where if my nose is too big or I’m too dark that I’m not going to be permitted to express myself. And I was luckily naive and didn’t realize that being a female director you’re dealing with a lot of other things. I totally wanted to be expressed and be in front of the camera and I just retreated into myself because of racism. And you know I prefer directing things. I don’t want to be in front of the camera. It’s very uncomfortable.

JO: I’m sad that you couldn’t be yourself in front of the camera, but at the same time I’m very glad you chose directing because you made a beautiful film and it is inspiring for other women. We need more so I’m so happy and I hope you make many more.

TO: Me too!

JO: And I hope that Hope is in them.

TO:She didn’t say this, but Hope is a filmmaker as well as an actress.

HOW: Tchaiko has inspired me so much. I think about when you first met me in 2010, I was so young and innocent. I mean I’m not this wild child now but I think that Tchaiko’s bravery, I think in terms of just speaking out about what she believes in and daring to be herself no matter how unconventional or just outside of the norm. I think that’s been an influence on me in terms of entertaining my own thinking and my own ideas and giving myself permission to do things that are not what people would expect. I moved to New York almost two years ago and I took a very extended break from acting for a while because I wanted to just write something and do something and direct something that spoke to my sensibilities. And it’s been an incredible experience. I made an anthology project. They’re multiple vignettes. There are 4 shorts. I aim to make 5 and the response has been phenomenal. I think that environment has been very good for me just because my whole life I’ve always felt odd and strange. But in New York, I feel like I’m not strange enough. And I think I needed that. The people are just like oh we like this idea rather than who’s attached. So I felt I’ve made a lot more progress as a storyteller in New York. I’m not sure where that journey is taking me in terms of if I’m staying there forever, but I have something tangible that I think hopefully speaks on my behalf. I’m working on my first feature script. I’m proud of myself for making a thing and even just going through that again. I always say look it’s a miracle anything gets made. The biggest lesson I’ve learned from watching Tchaiko over the years is that whatever you make you have to love it enough because you don’t know what that journey is going to be. So you better love it enough and it better be meaningful enough to you to stick through it because I’ve seen people jump on projects because oh well it ticks these boxes off or has these people in it and they’re miserable and end up quitting. But the thing that has kept me on this journey is, you know again talking about Tchaiko and seeing how much it means to her, and ultimately thinking about how great it is and it was worth it. It’s a story that’s worth being told. And so I have to ask myself that in everything I’m doing from now, oh this is a great opportunity but is it worth it?

JO: So much goes into a film. I’m always surprised when someone goes I want to write a horror movie because that’s what everybody is into right now.

HOW: Yes. And people live that way. Some people are saying this is what’s really trendy and just want to make money.

JO: I can’t do it. I just can’t.

TO: I think Hope and I have similar tenderness of spirit where it’s like we can’t show a fake love of something, of a project. I literally can’t. I will kill myself and I’m not being dramatic. I would probably relapse. It’s so claustrophobic for me not to be me. I just don’t get it. It has to have meaning to me.

JO: Well, Tchaiko and Hope it has been so great to talk to both of you! And I loved Solace. I hope to see many more films and I hope to see Hope films as well. But thank you so much!

Go to the official website for upcoming screenings http://www.solacefilm.com

About Solace:

At 17, Sole is mourning the death of her father while adjusting to her new life with her

overbearing grandmother in the Ladera Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. Desperate to escape, she discovers a performance art grant that would take her back to New York and the comfort of a familiar life. She recruits a pair of rebellious teenage neighbors, Jasmine and Guedado, to help her with the application and get her life back on track. But best-laid plans often go awry, and Jasmine’s volatile instability, the feelings Sole develops for Guedado, and her own secret battle with a destructive eating disorder, threaten to upend her plans and keep her trapped forever.

SOLACE is a moving and artful portrait of a smart, driven, and self-destructive teenage

orphan struggling to find her place. Tchaiko Omawale is a fresh filmmaking voice whose

unique storytelling style – one that is both visual and emotional – along with her sure-handed directing is a rare combination in a first feature. Led by Hope Olaide Wilson’s heartfelt performance and brave turn as Sole, SOLACE is a unique coming-of-age story that takes on the claustrophobic isolation of mental health issues with empathy and artistry.

Connect with Solace:

Official Website: http://www.solacefilm.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/solacefilm/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Solacefilm

Twitter: https://twitter.com/solacefilm